Kubrick’s executive producer for Full Metal Jacket discusses the practicalities of recreating the Vietnam war At London’s Lugubrious Beckton gasworks.

SPLENDOID: Generally, this site talks to the art people so the chance to get insights on the role of the Exec Producer role for a landmark picture from a landmark director is a very interesting proposition. To get proceedings going, could you give a brief overview of your responsibilities?

HARLAN: Making deals – getting permissions, clearing rights, hiring people at the right time and price. I find it actually quite banal to say since this is always the role of an exec. producer working for a powerhouse producer/director.

Banal for you, perhaps, but for us, it’s always interesting to know. People may not know that your relationship with Kubrick was actually familial as well as professional. I wonder if you both maintained a professional distance on set or if you allowed yourselves to be familiar in your working relationship?

The fact that he was my brother-in-law formed our personal relationship in 1964. When working with him post-1970 this didn’t ever come into it. It just can’t.

Full Metal Jacket was your 4th film working with Kubrick. Did your working relationship change over the course of those films? Did you find that things got easier as you got to know him better personally? Or perhaps harder because of the same?

Easier, since by this film I had gained much experience.

Were you on set often? Or was your job more office bound?

My office was always near the set – in a mobile home or even a VW bus.

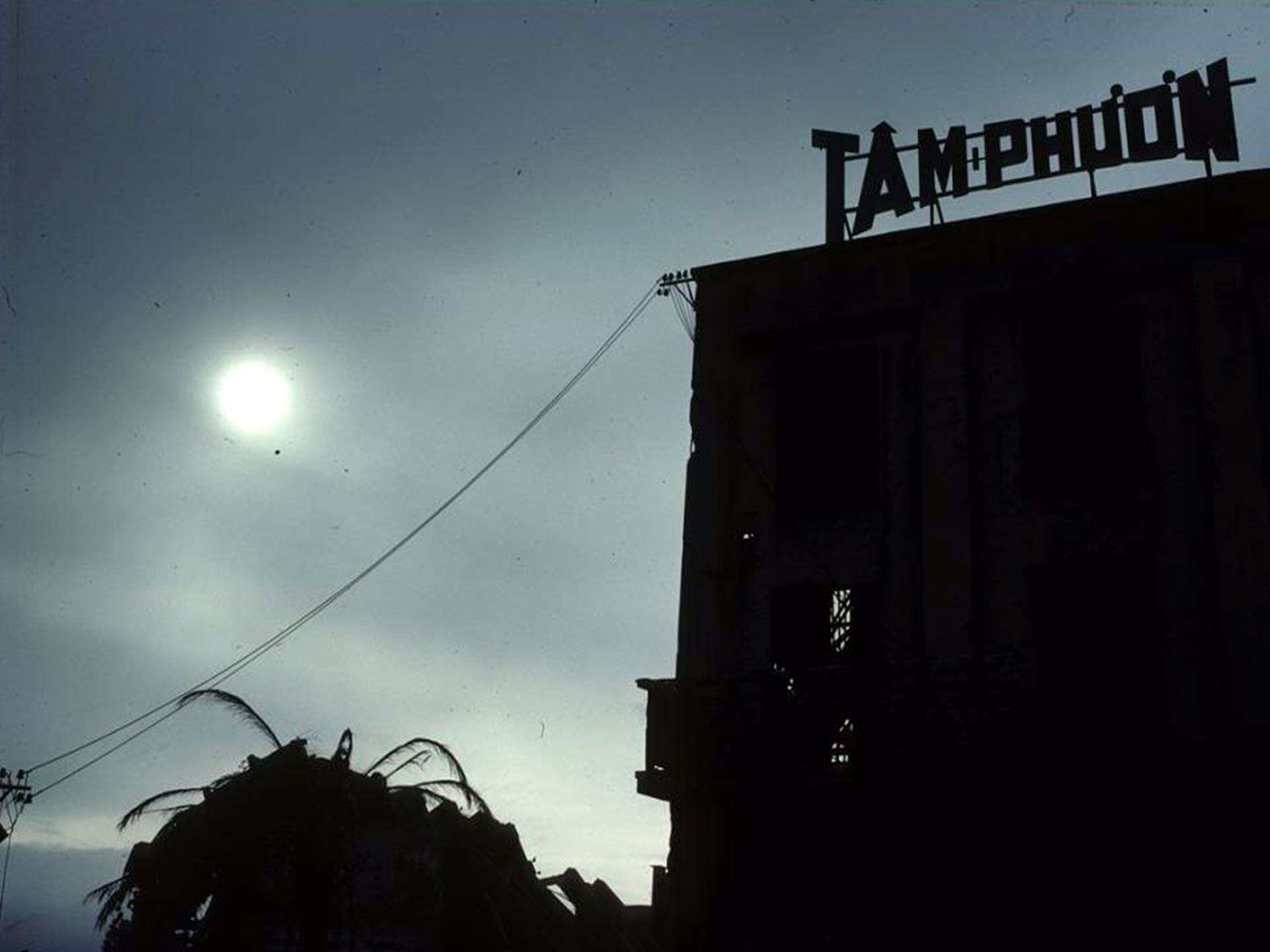

What inspired the choice for Beckton? Leon Vitali has said that the same architecture firm who designed Beckton designed industrial areas in Hué, which was, of course, the particular Theater of the Tet Offensive featured in the film*. Was that level of attention to detail serendipitous? Or was it more the case that Beckton was available and offered easy access? Indeed it was already being used as a filming location (Eons James Bond series had been there, an interpretation of 1984 had been filmed there, even John Wayne had filmed there for Brannigan)?

Leon’s answer was right. It was obviously close to home but was an ideal location in the sense that we could do whatever we wanted. The London horizon was covered with billboards, palm-trees, smoke, and fire. It had to look real, not realistic. The focus was on the handful of soldiers.

It was never regarded as a cut-price alternative to shooting in a Far East location?

Not by people who understood what the film was about. Beckton was a perfect setting for what Kubrick wanted to show.

So the production was quite budget conscious? A film like this would seem to require high production values and therefore there would be a lot of opportunities for the budget to escalate quickly?

Kubrick was a very responsible “trustee” and producer and didn’t want to waste Warner Bros. money. At the same time, the result had to be right by his standard – and Warner Bros. expected nothing less and never interfered.

So you didn’t have to work hard or cut corners to keep the art department within budget?

The cost is in time not in the art department. Not rushing, being self-critical and giving the actors time. The art department works to an approved plan and budget.

Was the process of securing the site heavily bureaucratic or relatively simple?

Not difficult since the authorities in charge of Beckton were very happy with someone else toppling buildings at their expense, buildings they wanted to get rid of anyway.

It’s well publicised that the shoot occupied the site for a very long time. Was there ever a danger of over-running your allotted tenancy agreement?

This wasn’t an issue.

The authorities in charge of Beckton were very happy with someone else toppling buildings at their expense, buildings they wanteD to get rid of anyway

How much of the site did the shoot actually take over?

The whole area of the former gasworks.

Did the site owners have to monitor what the production was doing on their property?

No. Not in this case. You could not “ruin” anything. This is not like filming in a stately home.

And how did the cast and crew feel about shooting at such a site as Beckton? An old gasworks doesn’t seem to offer the usual comforts of a studio.

The crew is there to identify with the aim of the filmmaker; nobody liked the dirt and dust in the old gasworks, but all relevant people saw the value in this choice.

When you first arrived on site what did you have to do to start to dress the site ready for filming?

Toppling buildings, installing billboards, digging big holes for palm-trees in skips, planting plastic shrubs, installing equipment for fire and smoke.

Of course, the palm trees. People always seem to be amused by the idea that you had to plant them in that part of London. How was this actually achieved?

Nothing special. They were bought from a place near Valencia and then driven on low-loading flat-bed trucks to Beckton and planted in skips.

When selectively demolishing areas of the existing buildings did you calculate the explosions to ensure that they fall in a certain way or was it more a case of just setting charges and seeing what happened?

We had specialists who managed to do this as instructed by the designer Anton Furst, who had drawn plans approved by Kubrick.

Did you work with Beckton management to determine what could be safely demolished or were they happy for you to get on with it?

They were satisfied as long as we only used professionals to do the demolition. They and we were fully insured and the owners had no possible liability in case of an accident.

In total, how long did it take to dress the area ready for shooting?

A few months – I don’t remember the exact time.

And what was the protocol after you finished shooting? Was there any stipulation as to how you had to leave it?

Not at all.

You mentioned Anton Furst was your production designer, why did you bring him on board?

Kubrick saw his earlier films, met him, liked him and made what was evidently the right choice.

Furst is quite a visionary in his own right. How was it working with him on your film?

He was great, had good ideas, was practical and managed to magic some Vietnamese atmosphere into the film. That’s what good production designers do.

In terms of approval for his design concepts and any final artworks what was the process? Did he work closely with Kubrick or was he generally left to work alone?

Anton proposed a set / a structure / dressing etc. and discussed it with Kubrick. This is the standard routine.

The “requirement” was that it must look “right and interesting”, not “wrong and interesting”.

It also had to be atmospheric, and achievable within the budget

With any historical recreation, there are very specific requirements. Firstly, how thorough was the production in ensuring the period authenticity of the dressings that were brought in?

The “requirement” was that it must look “right and interesting”, not “wrong and interesting”. It also had to be atmospheric and achievable within the budget. Don’t underestimate the professional skill of art-department crews – they can copy anything.

You made great usage of period billboards and signage. Were these sourced or recreated?

We had research photos (lots available) and then they were re-created by the art department.

Any other specific dressing elements that were used to help with authenticity?

French shutters – this used to be French Indochina.

What were you using for research material to guide all the above choices?

Books, newsreels from the Vietnam war. There is plenty available.

In the finished film, it feels like you were able to source a lot of period military hardware. How much of this was sourced and how much was recreated by the art department?

Not a lot. We had ONE flying helicopter with all the licenses needed. We had 3 authentic period tanks loaned from the Belgian army. Both the helicopter and the 3 tanks were squeezed like a lemon. It’s called film-making!

Did you use military advisors and/or veterans to help establish authenticity?

We had in our technical advisor, R Lee Ermey, an ex-marine-drill instructor who had also served in Vietnam. He trained the actors and extras who had to learn this complicated drill. He then also played the part, which was not planned.

What is your feeling on the set shoot now, looking back? Do you have positive remembrances or was it a difficult shoot?

It was difficult because it was sometimes very cold (for Vietnam) and it was always filthy. Shooting at Pinewood Studios is certainly more agreeable. But it looked great. The problem was never “the set” – it was the weather and the light but Kubrick and his crew did very well.

So you were you limited to only shooting on certain days?

With the weather it is not just good or bad, cold or warm, it is the light for continuity and cutting. The so-called “Magic hour” is what one is after, yellow sunlight and long shadows. And then add coloured smoke and artificial fog and filters.

Given that FMJ was Kubrick returning to the war genre with a Vietnam film at a time when a lot of pictures about the war were being made, to the point that they were fast becoming a sub-genre in their own right, and also given his artistic track record at that point, was there ever the feeling on set that you were making a film that could become a benchmark film in that particular canon, if not one of the great war films? Or does working with, as you put it, a powerhouse director like Kubrick mean that those kind of classifications are simply not applicable?

Artists don’t think like this. A serious and self-critical man like Kubrick will always do the best he can and hope that the result will find an echo in the public. This is never guaranteed. Films like Barry Lyndon or Eyes Wide Shut were hugely successful in Latin countries and in Japan, but not the USA or UK.

No artist can “plan” for this – any great artist has to please himself, or herself, first. Don’t forget: A man like Vincent van Gogh never sold a painting in his life, other than to bother Theo.

Of course, understood but I suppose what I am really trying to understand is whether these other films ever affected the productions collective design choices, in the sense that perhaps there was a feeling that you were under pressure to produce something better i.e. more authentic than Apocalypse Now, The Deerhunter, Platoon et al?

“No”,“yes,” and “no, not at all!” “Better than?” – forgive me, but this is a very amateurish question.

A serious and self-critical man like Kubrick will always do the best he can and hope that the result will find an echo in the public

Not at all. Thank you for being honest. I will try and reframe it. Given the success of the films I just mentioned – Platoon had even just won Best Picture at the Oscars – was there ever the feeling that your film was in competition, that the bar of what a war film could be and what it should look like had been raised in terms of how production design supports these particular narratives by conveying a realistic recreation of a well documented historical period?

As good as possible, is the right answer, given the limitation of a) a budget and b) that Kubrick avoided travel. Audiences who didn’t like Full Metal Jacket, would not have liked it better had the story been filmed in a lush jungle setting. It is irrelevant.

The substance is far more important than form. The film focuses on the abuse of young men and their destiny. Any war at any time in history could be used to tell this story.

But perhaps the fact that Platoon or Apocalypse Now were shot in the Phillippines straight away installed credibility as they matched what audiences recognised as that conflict from newsreel etc?

These were different films with different emphasis. Both excellent.

And to close, Full Metal Jacket has always been a film that divides opinion. We mentioned it earlier but do you see the film fitting into the canon of great Vietnam films or do you see it more as a standalone film and part of the Kubrick oeuvre?

All Kubrick films divided the critics and the audiences. All great artists share this problem, whether Beethoven, Turner, Picasso, Bergman or Kubrick. The film is not a great Vietnam film, it is a great war-film focusing on the young men who were used and abused.

Appendix:

* Interestingly, long time Kubrick collaborator Leon Vitali alluded to the fact, that the Beckton site was chosen due to the fact that the gasworks itself was designed by the same architects as also worked in Tao which gives the enterprise another level of resonance although I personally haven’t been able to find a reference and, in our interview, Jan Harlan also made no claim to that fact either.