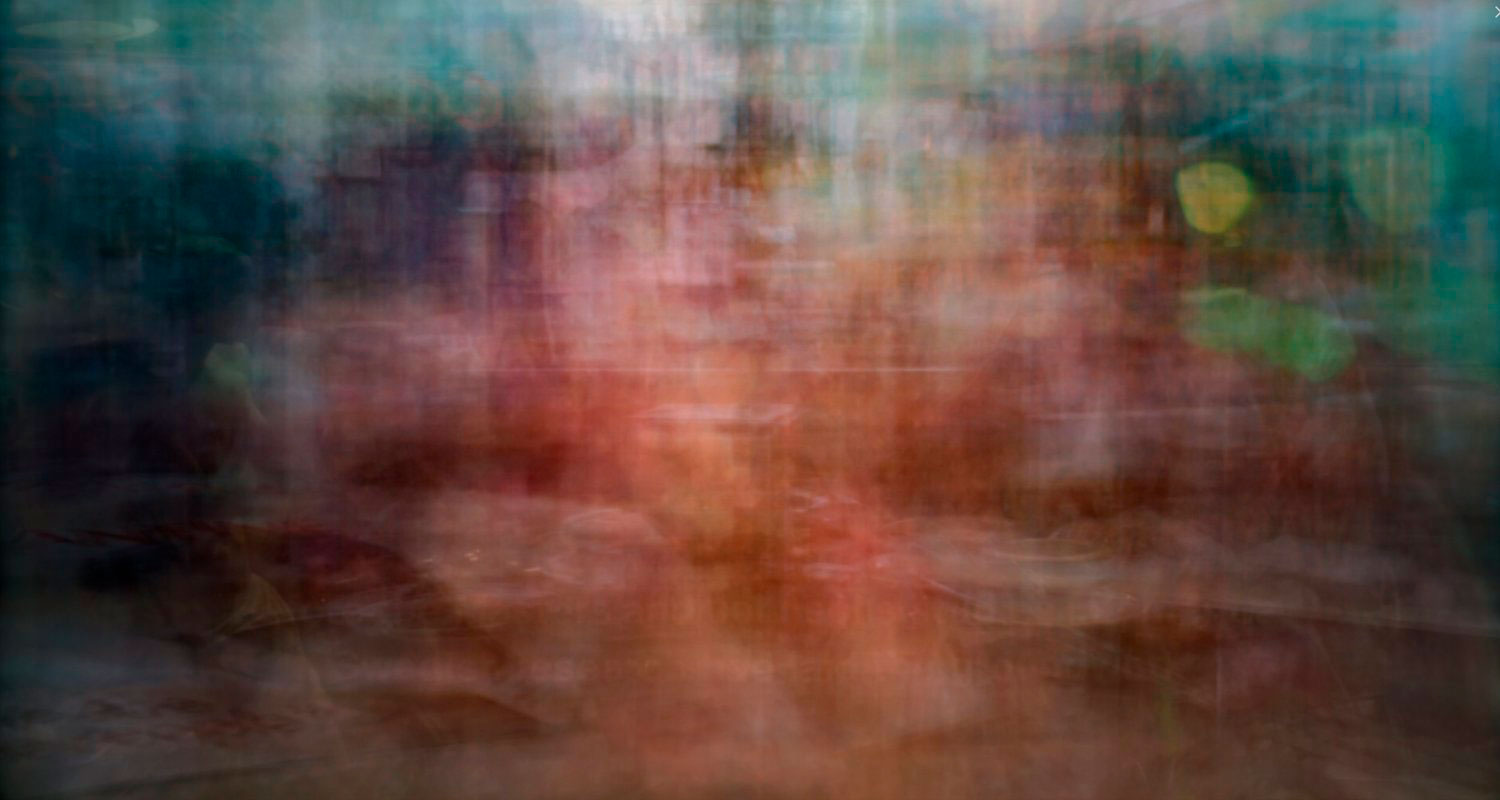

Jason Shulman is a UK-based mixed-media artist who created a global sensation with his striking images of complete feature films condensed into one frame to expose what he calls their ‘visual quintessence’.

We discuss the project in full, talking around its origins, making the inevitable Muybridge reference, and musing about whether cinema has an enduring magic that makes it a perfect subject for art.

SPLENDOID: Welcome to Filminutiae. To start at the very beginning. Where did the idea for photographing full feature films come from? It seems so simple and obvious and yet, in 120+ years of film history, I can’t think of it being done before?

JS: I started photographing short sporting events, then shot some rolling TV news. And then, obviously, the next thing had to be a film.

I was surprised that the simple idea of using a camera and a long exposure to photograph all of the light given out by a film had not been done a thousand times before. Amazingly it seems there are still gaps to be filled.

For example, and I’m not comparing the two processes at all, remember in The Matrix, the scene where the character is frozen and yet the tracking shot continues? This technique could have been resolved by Muybridge and his horse bet in 1878.

If he’d positioned all his cameras in a circle, instead of in a line, and then had the horse trip them simultaneously, he’d have invented it. But for some reason this blindingly basic idea took until 1999 before becoming a thing.

Quite. I suppose all that we can be sure of is that some things are created by accident, some by design. With his approach Muybridge was trying to solve a certain debate and ended up contributing to the invention of moving image, did you have any particular aim in mind for your project?

Curiosity.

Did you use any particular equipment?

A large camera and a large monitor.

You have mentioned in other interviews that it was the films that one might not have expected that produced the most interesting results. Of course, subjectivity being what it is, this will no doubt be different for every viewer. What was your expectation of the results? Anything like what you arrived at?

Before I photographed the first film I thought that all the light from all the different shots would probably produce something that looked like a dirty paint swatch. As we can see, this wasn’t the case.

Indeed. Quite the opposite in fact. Now, I am sure I know the answer but I have to ask, did you process or retouch the results in anyway?

There are no individual colour corrections. I don’t, say, bump up the blues. The final print is produced conventionally from a digital file.

I thought that all the light from all the different shots would probably produce something that looked like a dirty paint swatch. As we can see, this wasn’t the case

How did you select the films that you photographed? The choices seem very random but, perhaps, they were very distinct according to personal taste or some sort of system?

It turns out that most movies look remarkably similar rendered this way. At the start I tried to predict which films might make the most interesting marks. But it’s impossible. So I shot hundreds of films, anything that came to mind. Then stopped and chose the ones with interesting compositions, tones or tells.

The project has done very well online, published on your own site with many news sites then featuring it, but I believe it started as a physical exhibition at the COB?

Correct.

Where else has it been exhibited physically?

The White Noise Gallery in Rome. ‘Daydreaming with Stanley Kubrick’ in Somerset House, and at Photo London.

My favourite is The Wizard of Oz. I love how the Technicolor of the film has come through but in a somehow muddied form which, for me, seems to reflect the sinister aspects within the narrative but also the bad luck of the production history. There’s the legend about the Munchkin suicide, the spate of injuries during the making, Judy Garland’s personal difficulties and so forth. Which is your personal favourite and why?

Really? Munchkins topped themselves? I never knew that. No, I don’t have a favourite or if I do, then not for long. This week’s top 3 are…

Taxi Driver (1976) Because it could be its poster.

Digby, the Biggest Dog in the World (1973) Because of its inky translation of the antics of an enormous Sheepdog who got that way because he ate an untested fertiliser.

And The Gospel According to St Matthew (1964) Because in its gestalt a picture of Jesus appears. And that is like a mini fucking miracle.

As you have said, you see the images as exposing the “visual quintessence” of feature films. Were you inspired by other art that also deconstructs cinema? I ask this as many artists are inspired by film but artists that directly use feature films as media in their own art seem very rare. I am thinking specifically of Douglas Gordon’s 24 hour Psycho but I can’t think of many others. Perhaps there was other work you had in mind, maybe not even film related?

I can’t think of any cinema-based art that’s been an influence. I’ve always liked how the Futurists dealt with time and motion. Balla’s Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash is a wonderfully insightful painted take on the long-exposure. But it’s not really related.

I don’t think it’s a particularly culturally timely concept. Everyone from the Dadaists through Pop and the Post Mods could’ve taken something from these and slotted them into their argument

I don’t know, I feel that it’s somehow related in that it’s a painting emulating the effects of film. It’s interesting you should bring that up as what I love about your project is that it is uses photography in a similar way to how the Futurists and Cubists were using painting, this idea of capturing multiple images and perspectives in one, playing with time and space.

I also love that you are using photography in it’s purest documentary form, to record something visually using a mechanical process, and yet the results are anything but. Their root is the concrete object of a film, but the results are about pure form, colour and light and are very emotive to look at. They remind me of experiments into so-called ‘nothingness’ by colour field artists like Rothko, Barnet Newman, perhaps even late Turner and light artists like James Turrell?

This is a bit longwinded, I know. What I am trying to say is that with this thought in mind the pictures would seem to fit into the lineage of both Impressionism/Abstract Expressionism. I’d like to know if you personally view them fitting into that canon or are they something else for you?

I’ll give a short answer to your long question; threads are gathered, opinions formed. The history of art is never written by the artists, mainly because they can’t spell. I’d like to think I’m ‘ism’ free.

Do you think that there is something about cinema that makes it such an ideal subject for art?

It’s not ideal but it interests me for now.

OK. Going a bit further into that, do you think there’s something about our period right now that led to the work capturing the public imagination like it has? I wonder if it is because there is a massive weight of association on the project as we are on the cusp of new ways of making and consuming film, which is creating a mass nostalgia for old films, meaning people are currently lapping up anything to do with film history and traditional film culture?

I don’t think it’s a particularly culturally timely concept. Everyone from the Dadaists through Pop and the Post Mods could’ve taken something from these and slotted them into their argument.

But it is technologically timely. If you were to shoot a film this way from the back of a cinema the resulting photograph would have a hotspot in the middle that fades towards the edge of the frame. This is because of how light travels through the projectors lens, it splays it, and that makes getting an even exposure impossible. I photograph a big, practically pixel-free monitor that doesn’t splay. Something that’s only been around a few years.

That’s a good point. I hadn’t considered the importance of the monitor to the project. Interesting! Taking the point about technology in another direction, the work has had a massive success online and across social media, do you think there is something about the project that makes it right for these channels?

I have to admit I don’t know why the internet took to it so readily…but I’m glad it did.