I hear that she likes to dance around the room,

Two Doors Down, Mystery Jets, 2008

to a worn-out 12″ of Marquee Moon.

Popular music is the soundtrack to our modern lives. It is all around us, on the radio in the local shop, on the jukebox in the local hostelry, or drifting from a neighbour’s window. Like it or not, wherever we go ‘pop’ will be there .

‘Pop’ transcends all formal musical genres and encompasses all styles of music. That is not to say that it doesn’t have any kind of recognisable musical form of its own, however, ‘Pop’ can take the specific ‘voice’ (Toynbee, 2003) of any genre and apply certain conventions.

A piece of pop music will generally consist of strong rhythms and solid melodies organised in a conventional structure, and will have a mainstream style, in that it caters for the lowest common denominator and therefore does not need much interpretation (Adorno, 1998). This belies its main characteristic, above all a popular music text is a process (Toynbee, 2006), the end product of a production line, sold as a packaged commodity for consumption by a mass audience. (Negus, 1999). The sales figures in turn create the last important signifier, the ‘Pop Charts’ (Google, 2009), the rundowns of the best selling singles and albums in a given week that ultimately judge the success of a record.

How is this music created?

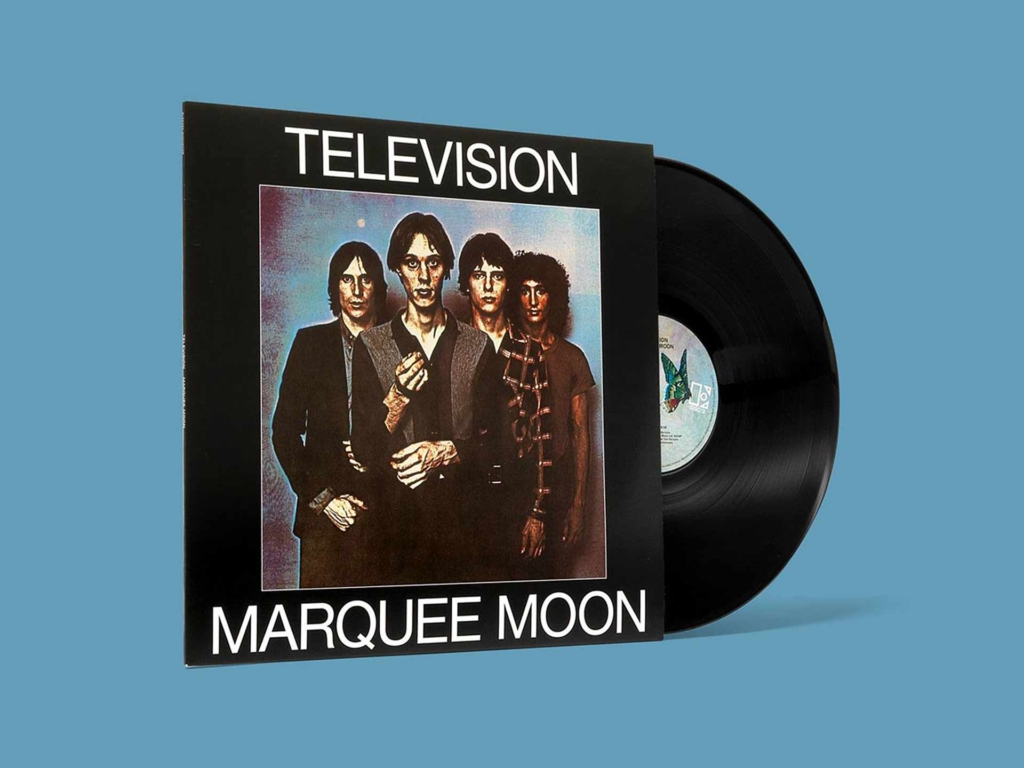

The lyric with which this essay commenced is from a recent ‘chart’ hit by a modern UK group but it references the 1977 12” single release of Marquee Moon, a recording by New York group Television. The manner in which the song is referenced is very sleight of hand, no explanation seems to be necessary. It could simply be an easy rhyme but the way in which the listener seems expected to understand and appreciate the reference suggests that more likely the inclusion is a way of enhancing the songs cultural capital.

This suggests that Marquee Moon is a recording worthy of study. A simple Internet search (Google, 2009) proves that the single, and the album on which it appears as the titular track, has been canonised by a cognescenti of critics, journalists, musicians and other culture industry professionals (Regev, 2006) and now obviously informs modern groups. I believe that as a case study text the album will be a useful tool to explore how different discourses of creativity inform the production of a popular music text.

The ‘Artistic’ Discourse

When discussing music as ‘Artistic’ we are talking about music that is performed by a wide range of individuals, whether it be the bedroom hobbyist, the semi-pro in local night-spots, or the professional musician working for a record label. All are united under the wider context of ‘culture’ or the “way of life and the actions through which people create meaningful worlds in which to live” (Negus, 1999, p20). In other terms, the artist is making music to fulfill a particular personal psychological need (Johnson, 2004) by creating ‘serious’ music that has a powerful message through which ‘people can be changed, minds opened’ (Reynolds, 1998, p466).

This specific approach can be found in our case study text. Television emerged from the 1970s bohemian underground scene in New York. The scene centred around CBGB, a nightclub where a disparate band of musicians, artists, fashion designers and hedonists bonded over a shared enthusiasm for ‘garage rock’1. A DIY lifestyle and fashion aesthetic started to build around the music, eventually being dubbed ‘punk’ when a fanzine of the same name emerged in 1975 (Kureishi & Savage, 1995). The various artists moved around the scene, falling into some groups and falling out with others. Television was no exception and after line up changes, much rehearsal and live performance the band were able to put together their debut album (Blake, 2006).

The debate around authenticity in music focuses on the origin, what was the catalyst for the creation of the text?

With this genesis, the artistic discourse and Marquee Moon could be said to be ‘authentic’ music. The debate around authenticity in music focuses on the origin, what was the catalyst for the creation of the text? The accepted benchmark are forms that can be read as true ‘popular music’, music that had honest intentions and was ‘of the people’, such as traditional folk or early Blues, neither of which were written or recorded but relied on being handed down by successive generations of musicians. The songs themselves are simple expressions of personal feelings or lyrical reportage on certain events. To extrapolate from that it is possible to say that all music with this origination, from Blues to punk and on into contemporary laptop-based electronica (for ‘artistic’ does not mean just analog), could be said to be truly ‘authentic’ in that all are handcrafted by artists for personal expression.

In the artistic discourse, the artists cannot always act alone. In order to get a larger audience for their creativity, some kind of distribution network is needed. A conduit is required that will present this creativity to the public sphere. This is where the record industry steps in. Under the guidance of an ‘Artist & Repertoire’ representative, new talent is tracked down and offered a recording contract before being nurtured to the point that they are able to purvey polished material to the wider world (Negus, 1992). In the case of punk the labels themselves could be seen to be part of the artistic discourse in that the companies associated with the bands were independent of the mainstream industry and thus were able to develop methods of handling artists that broke with the standard and became more centred around the musician (Hesmondhalgh, 2007). This independent spirit began to inform major labels who took on these new procedures. Elektra Records (part of the Warner Communications group) championed many underground bands and under their sponsorship Television released Marquee Moon in 1977 to great critical acclaim. The album title track became a no. 30 single in the UK but failed to attract a wide audience in America (Blake, 2006), (Last.FM, 2009).

The ‘Manufactured’ Discourse

When discussing the role of the record label we are at once introduced to the ‘manufactured’ discourse, where music is created not by the artist acting upon ‘a consciousness of self, stimulated by and embodying the artist’s own perceptions, thoughts, and feelings.’ (Kravit, 1992) but rather as a cultural form that has been commodified by an industry that manufactures and sells a product geared ‘toward people who are already receptive’ (Reynolds, 1998, p466). Record labels create their own artists and genres to appeal to the lowest common denominator in an audience that they view as being ‘blank receptors’ (Middleton, 2002, p6). This process is clearly illustrated by TV reality shows such as X-Factor. ‘Performers’ with raw talent are selected from thousands of hopefuls queuing up to ‘be famous’, not because they have any particular message to get across to the world but rather because they have seen the process at work and they themselves now wish to become ‘a star’. Once selected the performers are provided with their material, most likely written by paid songwriters, and shelved until someone suitable comes along to perform it (Negus, 1992). Finally, a compatible record producer will be assigned to the performer in order to obtain the best recording performance.

The actual musical process is the least important element. The manufactured performer must look right and will therefore be given an image that caters to a certain market

There is more to a popular music text than just the audio element, however. Dietmar Dath (2008) describes popular music as “a social practice concerned with emphatic modes of appreciating things, moods and situations. And an ‘emphatic mode of appreciation’ is, of course, something you can observe, you can see, not something on the side”. In practice, the actual musical process is the least important element. The manufactured performer must look right and will therefore be given an image that caters to a certain market, allowing marketing material to be targeted to the consumer (Negus, 1992). The performer themselves will be given a make-over and this new identity will also be assigned to their product. All sleeve design, press photography, MySpace pages, MTV idents, or any other material pertinent to them will be shaped into a cohesive ‘brand identity’ that is not that of the record label and is hopefully significantly different to make them stand out from other performers. This image will then be fed to the audience via the mainstream media (Negus, 1992) of music radio, TV, magazines, and now the Internet, all content-hungry mediums that need the fresh talent in order to satisfy their individual remits of being seen to have their fingers on the pulse.

Problems with the Two Tier approach

Linking both discourses is the idea of the ‘canon’. Whether the origin of a popular music text is artistic or manufactured, the process of recording and selling music to an audience with a taste for a particular genre or style will inevitably create a set of artifacts that are seen to be ‘the peaks of the aesthetic power’ (Regev, 2006, p1) of pop. With the important addition of passing time, the artefacts that survive in these unofficial lists for the longest time start to take on a mythical status. At this point they have become deified as part of ‘the canon’. Marquee Moon is one such text, evident by its inclusion in the countless chart rundowns (Rolling Stone, 2009) or its influence on modern groups.

This problematises the two-tier approach to studying popular music. A piece of music’s origin could be said to become largely unimportant when enough time has past as the pop canon consists of records created by artists and performers alike, and both are judged on equal merit.

Similarly the concept of ‘the artist’ and ‘authenticity’ has also become questionable. The manufactured discourse has no scruples with the commodification of existing talent. Initially for an artist personal expression is paramount but over time an artist starts to need the industry to spread their message further into the public sphere.

The concept of genre does not need

to be understood by the audience

but it is important that a text

is associated with a particular

use and pleasure.

In order to define a formula as to what sells best the recording industry needs a system. Musical ‘genres’ become useful (Negus, 1999) as a set of labels that are used to define the difference in voice between popular music texts but also to imply the different kinds of rewards that can be attained. The concept of genre does not need to be understood by the audience but it is important that a text is associated with a particular use and pleasure. (Hesmondhalgh, 2007).

Punk had what could be described as an ‘authentic’ genesis. Bands like Television created their own sounds autonomously. As that sound grew in popularity it became identified as a new genre (Blake, 2006) and as a marketable product. This demonstrates how A&R departments attempt to minimize risk by actively seeking new talent who fit a formula (Croteau & Hoynes, 2001) but at present are performing at a humble level. A potential to sell units is recognised and they are invited to sign a contract. This fresh, ungroomed artistic talent will then be submitted to the same ‘styling’ process as the cynical fame hungry hopeful of the audition room. Applied to punk it is evident that for every Television there was a spate of copycat groups (Blake, 2006). In this process ‘authenticity’ itself becomes a branding device. Punk had a reputation as being ‘from the streets’ and ‘of the people’. Record labels recognised this and utilised the punk vernacular as a stylistic device equally applicable to a musical text or an artist.

In this process the artists themselves are guiltless but it is the process itself that becomes ‘inauthentic’ causing the inevitable outcome that a musical scene will gradually homogenise (Croteau & Hoynes, 2001) and become full of performers and material that all sound the same in their imitation of that original, ‘authentic’ sound. Punk was no exception. As it grew in popularity it strayed away from its ‘artistic’ origins of ‘individualism, discovery, change’ (Reynolds, 1998, p466) and became a new musical orthodoxy. It is up to the audience to decide which is the best but as we can see illustrated in the concept of the canon, the further in time we get away from the originators the less the method of creation matters.

Debates around authentic music

and the artistic impulse are linked

with Romantic ideals of the artist

as sole creator

This idea of commodification raises the question, who is really the author of a popular music text? Debates around authentic music and the artistic impulse are linked with Romantic ideals of the artist as sole creator (Kravitt, 1992), a recognised genius figure whose involvement as an ‘author’ has the capacity to elevate the social status of a text (Foucalt, 1980). Indeed artistic discourse musicians may feel that they fulfill that criteria in themselves but then the question must arise, does a popular music text exist without the record company and the media machine behind them? The answer is perhaps in the moniker, a popular music text needs to be just that, popular, without an audience a text can be seen as an authentic personal expression but that is the limit of its influence, it is the exposure that it receives that can be said to make a text. This is perhaps the reason why so many hopefuls queue up for their chance of fame on the X-Factor?

That said artistic autonomy can subvert the process, authenticity can still prevail over the manufactured system. With a record such as Marquee Moon the expectations of the audience and the industry were confounded. The popular norm of the time was a public taste for highly polished Disco music, singer/songwriter type ballads or the overblown opus’ of the “prog rock’ movement. Punk was a reaction against all of these (Blake, 2006), a deliberate step back towards the ‘authentic’ essence of rock and roll; short, punchy songs delivered with a large amount of attitude. In turn audience expectation was for records that reflected this approach.

Television developed their own take on this by applying the punk vernacular but autonomously creating music that defied these new conventions. As an album of 8 songs, Marquee Moon is guitar-based music full of angular rhythms and somewhat uncommitted vocals, packaged with a ‘rough around the edges’ feel that epitomises its ‘garage rock’ origins. That said, rather than following the conventions of the 2-minute blazing pop song of the punk manifesto, much of the music opts for unconventional structures that owe more to Progressive Rock or Jazz, characterised by the playing of guitarists Tom Verlaine and Richard Lloyd who opted for complex interlinking solos. As an album, it starts with songs that follow a conventional verse/chorus structure, before dropping the 10-minute ‘jam workout’ Marquee Moon in the middle before returning to the song format once more, including the eventual top 40 hit ‘Prove It’.

Looking at the origination of the movement there is a case for Marquee Moon to be at the top of the punk canon, the most ‘authentic’ artefact. If punk is seen to stand for the unconventional, then releasing a record that subverted that particular maxim perhaps makes Marquee Moon the very definition of punk. The alternate view is that punk is more formal and by ignoring those specific conventions a record like Marquee Moon can in no way be deemed to be part of the punk rock genre.

A reality of the creation process is that

in the pursuit of larger audiences, the artistic discourse becomes compromised by the manufacturing process.

Whether originating from the ‘artistic’ discourse or the ‘manufactured’, the process of creating a popular music text removes the two-tier approach from the debate. A reality of the creation process is that in the pursuit of larger audiences, the artistic discourse becomes compromised by the manufacturing process. That said the manufactured discourse would not exist without the original artistic impulse that gave rise to the recognition that a cultural artifact can be commodified. The creative and artistic element is always needed but it is not as simple as the notion of the artist spreading his message into the world. In actuality, a complicated, integrated system of media practitioners all play their part.

A popular music text is a ‘product’, the result of an industrial process that designs a piece of recorded music as a physical or digital artefact to be bought and sold. The success of that product will be ultimately be judged by the audience on its release into the public sphere. The industry will only recognise a successful product as the one that sells the most units.

It is the nature of a music fan to endlessly debate a given song’s authenticity or why one is better than another, which music deserves to be at the top of the charts, and why certain ones don’t. This is reflected in the sheer number of music magazines, TV programmes, and Internet blogs dedicated to the discussion of the ‘canon’. Being that a pop record is a cultural artefact, this is a very subjective argument. There can be no right or wrong to the question of whether one record is better or more ‘authentic’ than another. It is the opinion of the listener as to whether they concur with a record’s origination or whether they don’t. Therefore every popular music text will have its fans because at the root of the argument is a record’s structural value. The audience only really cares about what pleasures the record can facilitate, does it make them want to dance around the room…?

Appendix

1. A back to basics approach, emerging in the 1960s. It was based on simple blues structures, performed on guitars and drums and played loudly with much enthusiasm and not necessarily any talent. Its defining characteristic was that it was a low fidelity form, in that its exponents used cheap equipment in unsalubrious surroundings such as band member’s garages.

References:

- Adorno, T.W. (1998) ‘On popular music’, in Frith, S. & Goodwin, A. (ed.) On record. London: Routledge

- Blake, M. (ed.) (2006) Punk: the whole story. London: Dorling Kindersley / MOJO

- Croteau, D & Hoynes, W. (2001) The business of media. Thousand Oaks CA: Pine Forge Press

- Dath, D (2004) ‘Introduction’, in Klanten, R. Hellige, H. Hulan, T. (ed) Sonic: visuals for music. Berlin: Die Gestalten Verlag

- Foucalt, M (1980) ‘What is an Author?’ in Bouchard, D.F (ed) Language, counter-memory, practice: selected essays and interviews by Michel Foucalt. New York: Cornell University Press

- Google (2009) Marquee Moon, Television

- Available at http://www.google.co.uk/search?client=firefox-a&rls=org.mozilla%3Aen-US%3Aofficial&channel=s&hl=en&q=Marquee+Moon%2C+Television&meta=&btnG=Google+Search (Accessed 25th March 2009)

- Google (2009) Top 50 charts

- http://www.google.co.uk/search?client=firefox-a&rls=org.mozilla%3Aen-US%3Aofficial&channel=s&hl=en&q=top+50+charts&meta=&btnG=Google+Search

- (Accessed 26th March 2009)

- Hesmondhalgh, D. ( 2007) The cultural industries. (2nd edn.) London: Sage Publications

- Johnson, S. (2004) Mind wide open. London: Penguin Books Ltd

- Kravitt, E.F. (1992) ‘Romanticism today’, The Musical Quarterly 76(1), pp. 93-109

- JSTOR (Online) Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/741914 Accessed: 19/01/2009

- Kureishi, H & Savage, J. (ed.) (1995) The Faber Book of Pop. London: Faber

- Last.FM (2009) Television

- Available at http://www.last.fm/music/Television/+wiki (Accessed 25th March 2009)

- Middleton, R. (2002) Studying Popular Music. (6th edn.) Buckingham: Open University Press

- Mystery Jets. (2008) Two Doors Down [CD] London: Sixsevenine.

- Negus, K (1992) Producing pop: culture & conflict in the popular music industry. (2nd edn.) Arnold: London

- Negus, K. (1999) Music genres and corporate cultures. London: Routledge

- Regev, M. (2006) ‘Introduction: Canonisation’, Popular Music, 25 (1), pp. 1-2 Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Reynolds, S. (1998) ‘New pop and its aftermath,’ in Frith, S. & Goodwin, A. (ed.) On record. London: Routledge

- Rolling Stone.(2009) The RS 500 Greatest Albums of All Time

- Available at http://www.rollingstone.com/news/story/5938174/the_rs_500_greatest_albums_of_all_time (Accessed 5th April 2009)

- Television. (1977) Marquee Moon [CD] London: Warner Brothers UK.

- Toynbee, J. (2006) ‘Making up and showing off: what musicians do’, in Bennet, A, Shank, B & Toynbee, J. (ed.) The popular music studies reader. Abingdon: Routledge