When I first saw the film I must admit to not being so impressed, something about it just felt a bit ‘off.’

Looking back today no doubt my critique was time-specific and generational. My first viewing of the film was no doubt coloured by inevitable comparisons to the swathe of other Vietnam pictures being released at the time, films that shared enough common traits as to establish the unofficial sub-genre of the ‘Nam film: a shorthand for depictions of sardonic grunts going about their particular branch of the war business on an incredible sliding scale of enthusiasm, ranging from psychopathic enjoyment to desperate helplessness soundtracked by a proto-hipster curated grabbag of period rock or classical music.

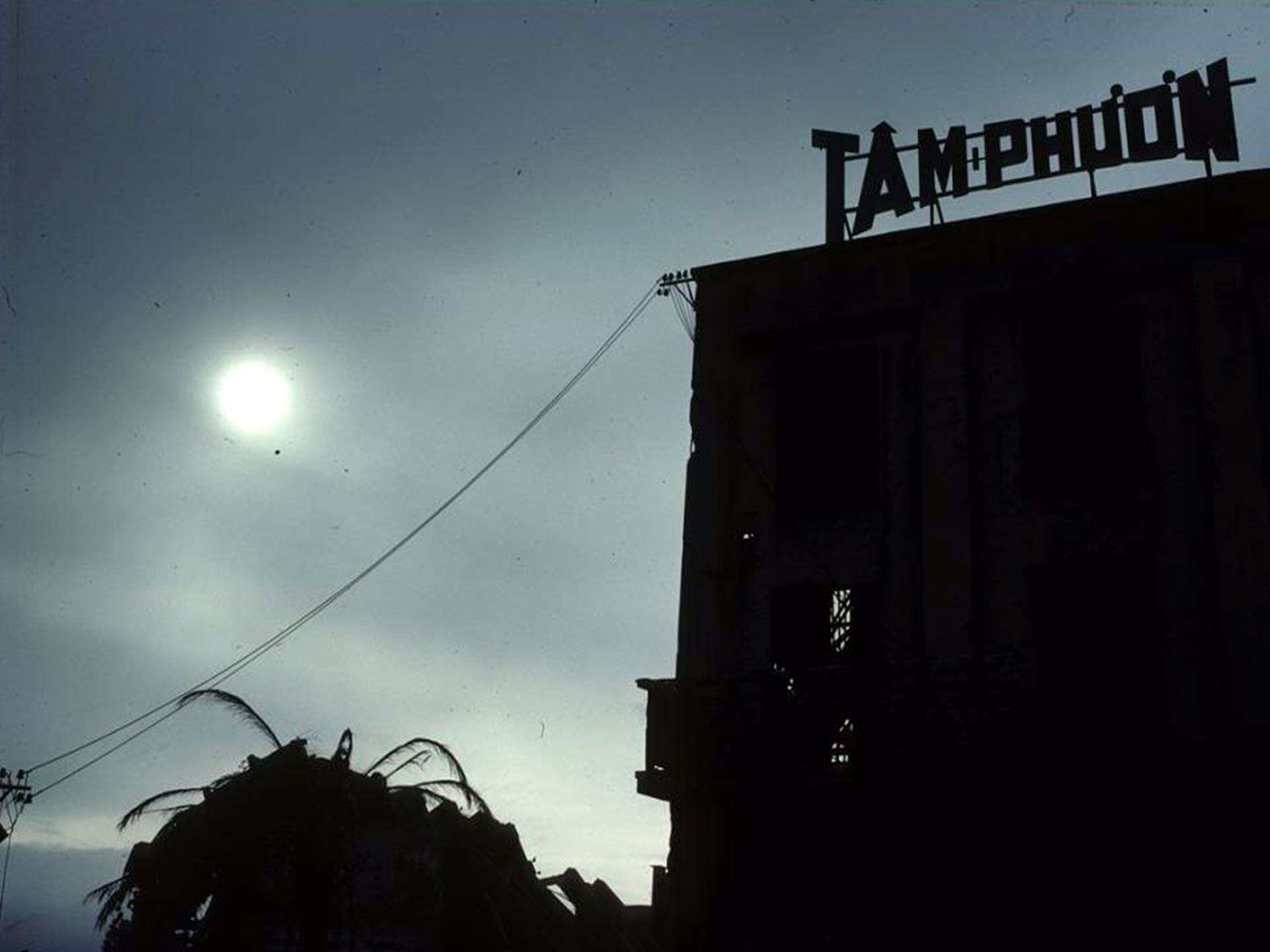

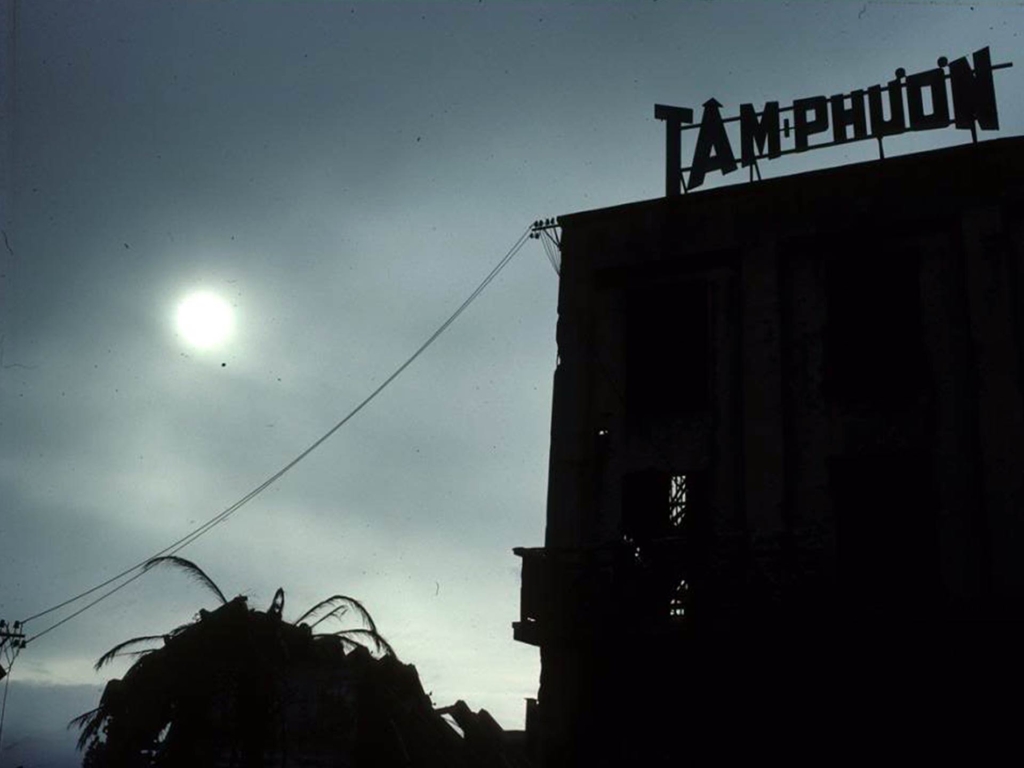

Full Metal Jacket bears the Kubrick trademark of being both adherent to and subversive of identifiable genre idioms, which might have been the parent to some of my difficulties with the movie. To get specific for a moment. The section in the boot camp I don’t mind, my problems begin when the raw recruits become boots on the ground. The most obvious difference to the other films in the Nam canon is that it isn’t a jungle combat film, but actually, this didn’t bother me. As an avid teen-reader of military history, I was very aware that Vietnam was not fought purely in the bush. In many ways, I was probably too aware. Whilst the second and third parts of the film are clearly shot on a real location, not in a studio, everything feels incredibly staged: the streets look too wide, the explosions and bullet strikes too perfectly timed, the black smoke in the background somehow too obvious…

Barry Lyndon

As a contrast let’s consider another Kubrick production with a strong war theme, Barry Lyndon. Despite being famously painterly in its mis-en-scene, the film feels somehow more believable, or less of a construct. One reason for this might be that the 18th Century paintings that inspired the films aesthetic are also the only material available with which we can compare and contrast the film. Whilst excellent visual sources they are not reliable sources of information in the scientific sense, as they themselves are works of art making their own representation of the period in which they were created. This makes the film highly simulacrumatic, in the sense that it is a representation of something that in itself is highly representational. The ultimate result for an audience is that means we can be more forgiving of the attempt at mediating reality of a film like Lyndon as we simply don’t have the material to hand to judge it against. For Full Metal Jacket the opposite is true, there is a wealth of archive visual material and so it is incredibly easy to find documentary photographic evidence to compare with including the ones that were the productions own source material.

Presumably, our assumption is that a photograph

is free from the kind of direct physical/emotional

engagement evident in hand-rendering

and so it is less guilty of skewing reality

Photography as witness

The public mind tends to hold photography up as being the absolute benchmark of authenticity simply because a still or moving photograph is the result of a mechanical process We collectively agree that the result of light hitting a chemically treated substrate is better able to mediate reality than somebodies brain operating a hand holding a pencil. Presumably, our assumption is that a photograph is free from the kind of direct physical/emotional engagement evident in hand-rendering and so it is less guilty of skewing reality. In simple terms, the more a drawing looks like a photograph, the more we read it as being a ‘better’ representation of its subject.

In his excellent book, The Reality Effect, author Joel Black makes the suggestion that for the majority of the global populace the 20th Century was largely experienced via the moving image. He posits the thought this has had the effect of re-framing our feeling as to what actually constitutes reality, to the point that if our tangible physical experiences don’t appear to measure up to what we expect from having seen similar events on-screen then we start to question how ‘real’ or ‘good’ those experiences actually have been.

Staging Warfare

War is something that the majority of people today will only experience visually via news footage (‘official’ or self-captured) or in a movie. In that sense, the screen version of reality now sets the bar for the actuality of war. A very obvious example of this can be found in the reportage of 9/11, an event that was often described by everyday people, ( i.e. not military, police or national security) as ‘looking like a movie’.

To take the point further, let us refer to a benchmark piece of archive material. One particular instance springs to mind: Roger Fenton’s famous ‘Valley of Death’ photograph from the Crimean war. In this image we see a battlefield after the fact, a stark landscape littered with fallen cannonballs. It would be easy to see this as one of the ultimate representations of war. But we also have to consider another reality of this image, that there was a certain amount of construction before the exposure of the plate – Fenton moved cannonballs to amplify the drama and thus satisfy his imagination and that which he expected of the public back home. The reality of war in this instance became a manufactured image which is the one that found its way into the historical record.

we have become desensitised to the actual

horrific effects of war, to the point, that a depiction

of the real thing now looks like false

Moving forward to more recent history, an image such as Ken Jareke’s immolated corpse from his Highway 8 reportage from the 1st Gulf War conflict was controversial when first published for its uncompromising depiction of the reality of warfare. We might argue now, some 30 years later, that due to our exposure to ever increasingly ‘real’ looking elements of gore in make-up and CGI elements in popular films we have become desensitised to the actual horrific effects of war, to the point, that a depiction of the real thing now looks like false.

Let’s look at the opposite side of the spectrum and consider whether the ultimate manufactured representation can become reality? For this, we can look at a theatre performance. It has the benefit of actual live human performances to confuse the intelligence and satisfy the physical elements necessary for suspension of disbelief, but its staging will be forever be framed by the proscenium arch or the audience of the round. Therefore, reflexivity is inherent in the medium in the sense that performance makes itself very clear that it is a piece of art and nothing else. A piece such as Warhorse uses a wide range of technical effects but it is still ultimately expressionistic whereas a piece such as Journey’s End is resolutely more ‘realistic’ in that it is comparatively small scale and unfolds in close to real time and yet it too is clearly a staged performance. And yet both manage to stir incredible emotions in an audience. Could be that it be that both are so emotive and affecting precisely because they are not archive material?

What is real anyway?

Which brings us back to Full Metal Jacket and the question of the reality that the film is trying to present. Realism is only attributed through what we directly experience which, when it comes to war, is something that the majority of people in our times have not experienced. Therefore, it has to be noted that the common perception of war is one that has largely been mediated to us via film, theatre, and literature.

Like the stage plays Full Metal Jacket is showing a retrospective impression of the Vietnam war. It attempts to create just enough of a sense of actual time and place that it is able to communicate its message: that war is complicated; that people on both sides will have their humanity abused by the state, and so forth. As it is a feature film, made using photography, not a live performance, its reality effect is heightened through the fact that it is moving image but at the same time it is a constructed fiction and by default can also, therefore, be dismissed as being ‘non-realistic’.

It, therefore, stands as an open invitation to consider whether a narrative film can approach anything near an authentic representation of something that most viewers will not have experienced first-hand. An important fact to note is that veterans of Vietnam and other Theaters hold the film up as being one of the most authentic cinematic recreations of military life, both on the home front and on the front line. But we might, at this point, go so far as to question what is exactly the reality of war? There is enough documented evidence of soldiers through the ages entering altered states of perception, either through abject fear, excitement or, indeed, drug use (either recreational or, as recent historical findings are suggesting, state-supported drug administration) that would seem to make any attempt to make a concrete definition somewhat difficult. In that reading, Kubrick’s slightly surreal/hyper-real/ approach for the film becomes a very apt response.

And of course, the ultimate test for my initial hypothesis of the film, would I have liked it any better if it had been an objective documentary shot within the actual ruins of Hué City?